Restoration document:

I've been restoring old houses in Minneapolis since 1976,

with an interest in the permanence of the restoration.

I've done 100 percent paint removal and recoating on scores of

large houses, using heat guns. I use only Ben Moore Element

Guard or Sherwin Williams Duration. I also perform the

carpentry tasks.

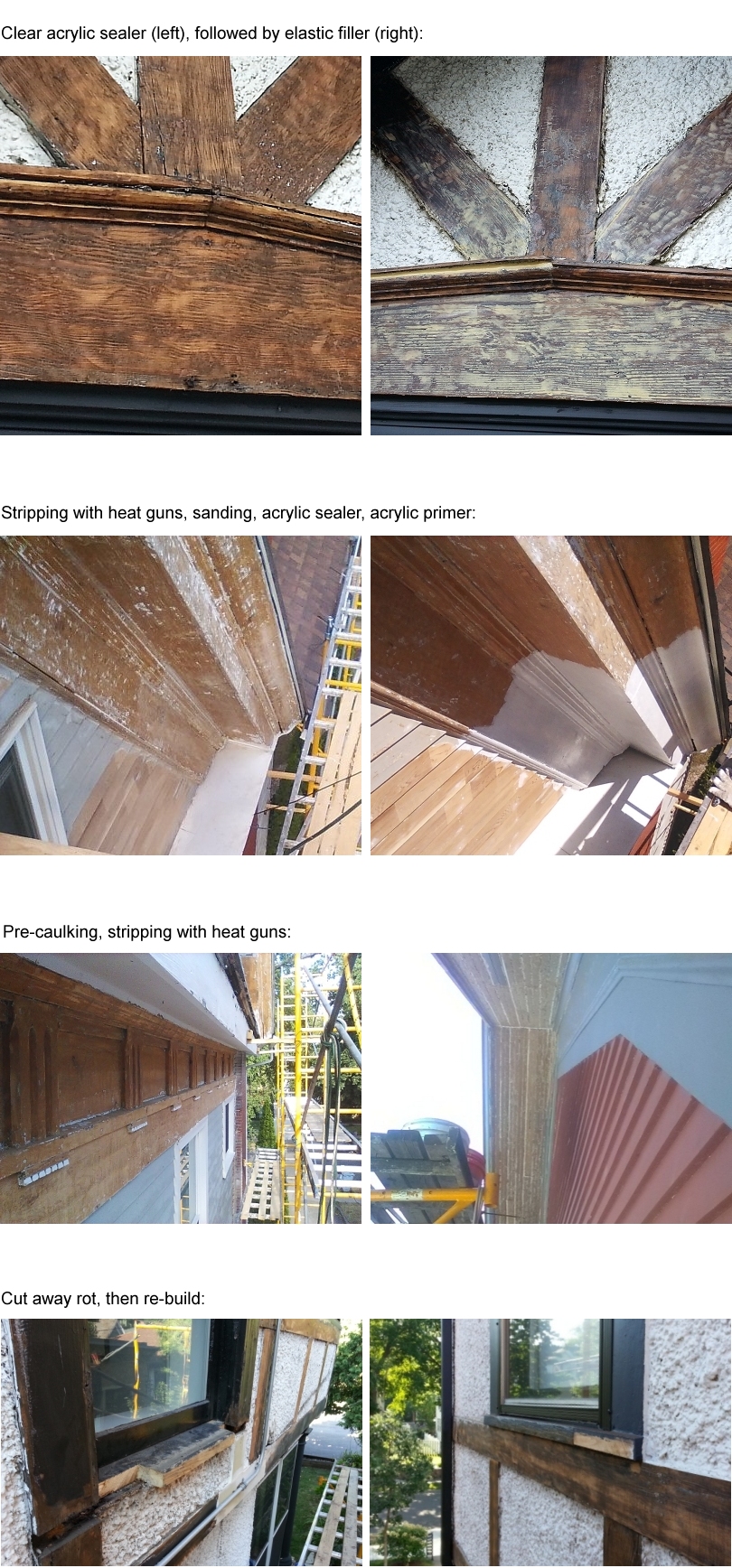

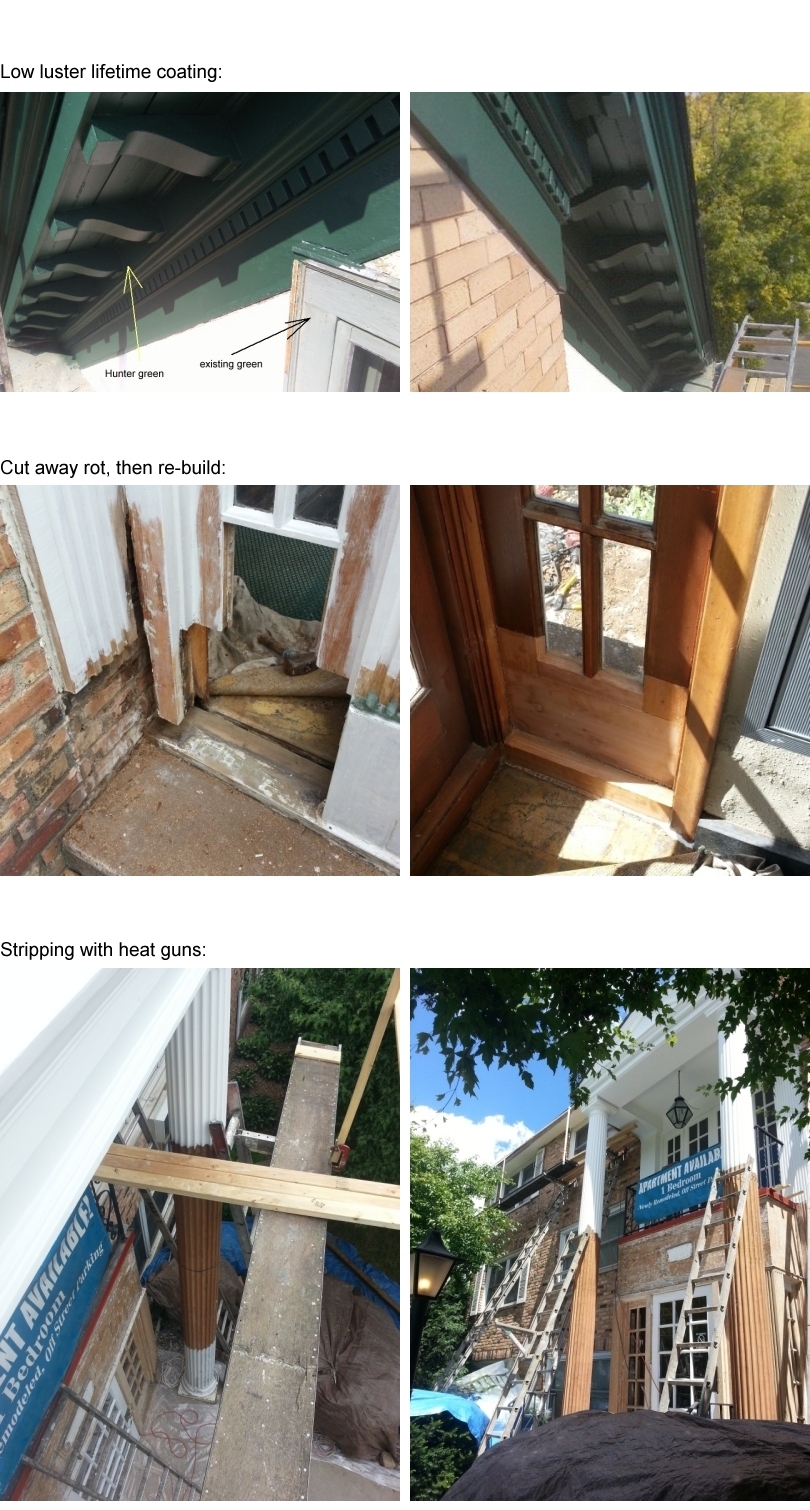

The photo above and below is my standard fare on exteriors.

I've been restoring old houses in Minneapolis since 1976,

with an interest in the permanence of the restoration.

I've done 100 percent paint removal and recoating on scores of

large houses, using heat guns. I use only Ben Moore Element

Guard or Sherwin Williams Duration. I also perform the

carpentry tasks.

The photo above and below is my standard fare on exteriors.

Part I

Tools and techniques for using heat to completely remove

paint from siding and trim.

1. Ground Cover

2. Scaffolding

3. Face Mask and Clothing

4. Surface Preparation - Heat Guns

5. Pro-Prep Scrapers

6. Setting Nails

7. Hand Sanding

Part II

Materials and techniques for coating bare wood.

8. Soaker Coat

9. Caulk

10. Acrylic Primer

11. Finish Coats

12. Encapsulation

13. Overpainting

Part I

Paint removal

1. Ground Cover

Protecting the health of your customers, their neighbors,

their pets and wildlife is the motivation for containing

lead paint chips and dust.

Cover the ground with 4 mil plastic sheeting, cutting

and fitting tightly around bushes. Hang nylon tarps over

bushes, and remove these each night. Use plenty of ballast

to secure the ground cover. After paint removal, slice it

into manageable sections and roll it up.

Vacuum up any remaining chips using a wide diameter

vacuum hose with a tapered attachment. This will

prevent clogging the hose with chips and twigs.

2. Scaffolding

You'll be far more productive working off a plank

than off a ladder. Every house scaffolds differently,

and a lot of thought must be given as to exactly

how to implement it. Whether you rent or own your

scaffolding, you'll find adjustable stands and sidearms

for planks to be indispensable accessories.

Scaffolding will also provide a means for hanging

tarps to help direct chips and dust downwards to the

ground cover.

3. Face mask and clothing

The motivation here is to protect yourself with a mask,

and to protect people and pets you come in contact with

by changing clothes at the jobsite.

I've been using charcoal canister breathing filters.

These seem to be effective, since lead has a definite

odor when melting old leaded paint using heat guns,

and these filters block out all such odor. There

is a filter called ULPA (Ultra Low Penetration Air)

which apparently is the ultimate protection against

lead fumes, but don't look for it at your paint store.

Eyes can also absorb lead fumes, so you might want to

consider full face protection.

Beginning in 2022, I've been using a mask with no

filter. With duct tape, I've attached shop vac hose

to a mask that originally used charcoal cannisters.

With the ends of the hoses dangling well below the

heat guns (and of course lead fumes rise along

with the heat), I'm breathing good air.

Hopefully, you'll do a better job than I do at

forming a good seal to your face. Being clean-

shaven and using Vaseline as a sealant is key:

4. The heat gun

4. The heat gun

I've carefully measured stripping progress using single,

double and triple heat guns, and consistently find that

double heat guns strip at exactly twice the rate of single

guns, and triple heat guns strip at exactly triple the rate

of single guns.

Triple guns work well for siding. I buy the thirty-dollar

guns at Menards or Home Depot, remove the plastic casing

from two of them, and through the use of electrical or

duct tape, achieve the configuration in the photo. By

doing this and by fastening the cords at your waist, you

will reduce the weight to exactly that of two heat guns.

A very important modification of the nozzle is to make about

a dozen snips and flare out the resulting sections as shown

in the photo. This will not only spread the heat out more

uniformly on the surface to be stripped, it will also allow

you to hold the nozzles right up against the surface and

keep them there. The biggest mistake workers make when

using heat guns is that they tend to keep backing the gun

away from the surface. The nozzles should rest on the

surface 100 percent of the time you are stripping.

Work in long strips. Heat spreads through the paint film

by conduction. If you work in short strips, you lose this

advantage of preheating. You also lose this advantage

every time you back the gun off the surface.

Double heat guns work well for trim and siding. Simply tape

two guns together.

Each heat gun requires a separate electrical circuit. Have

lots of cord on hand. Each 1000 watt gun costs fifteen cents

per hour to run. Thus, a triple gun costs less than four

dollars per day to operate.

Fire hazards

Heat stripping does not need to be a risky procedure. The

most important thing is to carefully caulk all cracks,

holes and gaps between boards before using heat. Carefully

inspect under each siding board as well as all other boards

for gaps, holes or cracks.

Hidden fires in walls, eaves and under shingles start

in two ways:

1. Heat flowing into cracks, holes or gaps.

There is very dry wood or even dry wood dust in

walls, eaves, and at the roof line. This can

begin to smolder without your knowledge and erupt

into flames after you've gone home.

2. Sparks emitted from heat gun nozzles drift into

cracks, holes or gaps.

Bits of paint shavings fall into the nozzles and

come out as sparks, particularly when melting on

the underside of a horizontal surface, such as a

soffit.

You can virtually eliminate the risk of fire by using caulk

to fill in any cracks, holes or gaps prior to heat stripping.

This is my standard procedure. Never aim your gun at or below

any crack, hole or gap.

One place that cannot be caulked is where the roof shingles

meet the fascia board. Stay well away from the roof line

when heat stripping. Dry scrape the upper couple inches of

the fascia board.

Whenever in doubt, turn the guns down to the low heat setting

or back them well away from the surface and use a little extra

scraping muscle.

Keep a water hose with nozzle attachment, a hammer and a

pry bar near you on your scaffolding. The hose should be left

on at the spicket. (A small fire extinguisher is very handy.)

In the event of a fire, do not pry up any board until you have

the hose in hand. Prying up a board gives the fire a burst of

oxygen and sudden life, causing it to spread rapidly.

4.5 Infrared heat (radiant heat) for paint removal

Another possibility to consider:

A lightweight infrared heater using just one electrical

circuit strips paint nearly as fast as my triple circuit

heat guns, provided there is reasonable continuity of the

paint film to be stripped. I began using infrared heat

occasionally, beginning in 2004, after being alerted to it by

a reader of this website. It's been a nice compliment to

my old standby conventional heat guns. The drawback is that

there is a slow initial heat transfer to the substrate,

meaning it is all the more important to keep the tool on

the substrate continuously.

I haven't seen evidence of any fire hazard with it (but

still use caution), and little or no need of a face mask.

Why no one thought of this for paint removal 50 years ago is

hard to understand. The technology is at least that old.

There is a commercial model available, but I didn't want

to spend $465 on the heavy commercial model when I could

make a lightweight model for about $50 in materials and

30 minutes of my time. I converted an old infrared room heater

for which I had paid about $50 into a very lightweight paint

remover. The replacement tubes are only $10 (and I have yet to

burn out a tube).

My tool works as well as the commercial model. The working

parts in my tool are the same as in the commercial model -

two quartz tubes.

Go to wbmarvin.com for a listing of available infrared

heaters and the $10 replacement tubes. The model 5460

Steam 'n Heat at $79.95 looks like the current version of the

old Marvin heater I had used to make my paint remover. You

might also check at Walmart or search online for inexpensive

infrared quartz room heaters.

Make your own infrared paint remover and save the weight and

the high cost of the commercial model. The commercial model

(Silent Paint Remover) weighs 4 lb 3 oz. My infrared paint

remover weighs just 1 lb 12 oz. This includes the 12 oz

clamp being used for the handle. A lighter handle, such as

a simple L-shaped piece of wood will bring the weight down

to just 1 lb 1 oz. Having stripped paint for a living for

the past 50 years using heat guns, I can assure you that

you'll appreciate this weight reduction and increased

productivity.

I've carefully measured stripping progress using single,

double and triple heat guns, and consistently find that

double heat guns strip at exactly twice the rate of single

guns, and triple heat guns strip at exactly triple the rate

of single guns.

Triple guns work well for siding. I buy the thirty-dollar

guns at Menards or Home Depot, remove the plastic casing

from two of them, and through the use of electrical or

duct tape, achieve the configuration in the photo. By

doing this and by fastening the cords at your waist, you

will reduce the weight to exactly that of two heat guns.

A very important modification of the nozzle is to make about

a dozen snips and flare out the resulting sections as shown

in the photo. This will not only spread the heat out more

uniformly on the surface to be stripped, it will also allow

you to hold the nozzles right up against the surface and

keep them there. The biggest mistake workers make when

using heat guns is that they tend to keep backing the gun

away from the surface. The nozzles should rest on the

surface 100 percent of the time you are stripping.

Work in long strips. Heat spreads through the paint film

by conduction. If you work in short strips, you lose this

advantage of preheating. You also lose this advantage

every time you back the gun off the surface.

Double heat guns work well for trim and siding. Simply tape

two guns together.

Each heat gun requires a separate electrical circuit. Have

lots of cord on hand. Each 1000 watt gun costs fifteen cents

per hour to run. Thus, a triple gun costs less than four

dollars per day to operate.

Fire hazards

Heat stripping does not need to be a risky procedure. The

most important thing is to carefully caulk all cracks,

holes and gaps between boards before using heat. Carefully

inspect under each siding board as well as all other boards

for gaps, holes or cracks.

Hidden fires in walls, eaves and under shingles start

in two ways:

1. Heat flowing into cracks, holes or gaps.

There is very dry wood or even dry wood dust in

walls, eaves, and at the roof line. This can

begin to smolder without your knowledge and erupt

into flames after you've gone home.

2. Sparks emitted from heat gun nozzles drift into

cracks, holes or gaps.

Bits of paint shavings fall into the nozzles and

come out as sparks, particularly when melting on

the underside of a horizontal surface, such as a

soffit.

You can virtually eliminate the risk of fire by using caulk

to fill in any cracks, holes or gaps prior to heat stripping.

This is my standard procedure. Never aim your gun at or below

any crack, hole or gap.

One place that cannot be caulked is where the roof shingles

meet the fascia board. Stay well away from the roof line

when heat stripping. Dry scrape the upper couple inches of

the fascia board.

Whenever in doubt, turn the guns down to the low heat setting

or back them well away from the surface and use a little extra

scraping muscle.

Keep a water hose with nozzle attachment, a hammer and a

pry bar near you on your scaffolding. The hose should be left

on at the spicket. (A small fire extinguisher is very handy.)

In the event of a fire, do not pry up any board until you have

the hose in hand. Prying up a board gives the fire a burst of

oxygen and sudden life, causing it to spread rapidly.

4.5 Infrared heat (radiant heat) for paint removal

Another possibility to consider:

A lightweight infrared heater using just one electrical

circuit strips paint nearly as fast as my triple circuit

heat guns, provided there is reasonable continuity of the

paint film to be stripped. I began using infrared heat

occasionally, beginning in 2004, after being alerted to it by

a reader of this website. It's been a nice compliment to

my old standby conventional heat guns. The drawback is that

there is a slow initial heat transfer to the substrate,

meaning it is all the more important to keep the tool on

the substrate continuously.

I haven't seen evidence of any fire hazard with it (but

still use caution), and little or no need of a face mask.

Why no one thought of this for paint removal 50 years ago is

hard to understand. The technology is at least that old.

There is a commercial model available, but I didn't want

to spend $465 on the heavy commercial model when I could

make a lightweight model for about $50 in materials and

30 minutes of my time. I converted an old infrared room heater

for which I had paid about $50 into a very lightweight paint

remover. The replacement tubes are only $10 (and I have yet to

burn out a tube).

My tool works as well as the commercial model. The working

parts in my tool are the same as in the commercial model -

two quartz tubes.

Go to wbmarvin.com for a listing of available infrared

heaters and the $10 replacement tubes. The model 5460

Steam 'n Heat at $79.95 looks like the current version of the

old Marvin heater I had used to make my paint remover. You

might also check at Walmart or search online for inexpensive

infrared quartz room heaters.

Make your own infrared paint remover and save the weight and

the high cost of the commercial model. The commercial model

(Silent Paint Remover) weighs 4 lb 3 oz. My infrared paint

remover weighs just 1 lb 12 oz. This includes the 12 oz

clamp being used for the handle. A lighter handle, such as

a simple L-shaped piece of wood will bring the weight down

to just 1 lb 1 oz. Having stripped paint for a living for

the past 50 years using heat guns, I can assure you that

you'll appreciate this weight reduction and increased

productivity.

I refolded the aluminum reflector so that the tubes would

be spaced 2 1/2 inches apart, which is the average spacing

of narrow lap siding.

I also made a single tube model for doing narrow architectural

detail.

Neither the aluminum reflector or the clamp get too warm

to cause any problem. I casually lay the tool down facing

up and running (meaning plugged in - no switch needed) when

I'm not using it. You can lay it down on any surface such

as a wood plank, the ground, or a nylon tarp.

5. Pro-Prep scrapers

I refolded the aluminum reflector so that the tubes would

be spaced 2 1/2 inches apart, which is the average spacing

of narrow lap siding.

I also made a single tube model for doing narrow architectural

detail.

Neither the aluminum reflector or the clamp get too warm

to cause any problem. I casually lay the tool down facing

up and running (meaning plugged in - no switch needed) when

I'm not using it. You can lay it down on any surface such

as a wood plank, the ground, or a nylon tarp.

5. Pro-Prep scrapers

These scrapers will not only greatly boost your heat stripping

output, they will be your partner in all kinds of dry scraping

endeavors, from high speed outdoor dry paint removal to fine

interior wood refinishing projects, including furniture.

Proper sharpening and use of these scrapers is at the heart

of indoor and outdoor refinishing projects. The blades shown

above will be your primary ones for outdoor work (and most

indoor work). For heat stripping, I use the small sized

handles even with the large sized blades. This gives greater

clearance for shavings.

Buy large coarse grade files by the half-dozen, or by the

dozen if you have a helper. A sharp file is the only tool

to use to sharpen your scraper. As soon as filing becomes

a bit of a struggle, throw the file away.

These scrapers will not only greatly boost your heat stripping

output, they will be your partner in all kinds of dry scraping

endeavors, from high speed outdoor dry paint removal to fine

interior wood refinishing projects, including furniture.

Proper sharpening and use of these scrapers is at the heart

of indoor and outdoor refinishing projects. The blades shown

above will be your primary ones for outdoor work (and most

indoor work). For heat stripping, I use the small sized

handles even with the large sized blades. This gives greater

clearance for shavings.

Buy large coarse grade files by the half-dozen, or by the

dozen if you have a helper. A sharp file is the only tool

to use to sharpen your scraper. As soon as filing becomes

a bit of a struggle, throw the file away.

Place the scraper on a firm surface and file into the blade

edge. File at a 45 degree angle. Slightly round the corners

of the large flat blades as shown in the drawing; and for

dry scraping, very slightly arc the entire edge as shown.

Rounding the corners will help keep you from making gouge lines

on the surface you're scraping. Arcing an edge will give you

better bite for dry scraping.

Keep your file with you at all times. Dry scraping necessitates

resharpening as often as every half minute. Heat scraping

necessitates resharpening about every five minutes.

Use a variety of motions with your scraper - towards the guns

with the grain, away from the guns with the grain, perpendicular

to the grain, and diagonal to the grain.

Take your time and let the heat do most of the work, or

you'll end up with gouges on your wood surfaces. Clean up

all residue as you go along.

Heat assisted scraping is usually the best approach even

when just spot scraping. It's gentler on the wood and will

allow you to feather the paint as you go along.

Retire your blade as soon as it becomes a bit of a chore

to sharpen it. (You get to the thicker part of the blade

as you sharpen it.) The cost of the files and scraper

blades is small compared to the cost of struggling with

expended files and blades.

Place the scraper on a firm surface and file into the blade

edge. File at a 45 degree angle. Slightly round the corners

of the large flat blades as shown in the drawing; and for

dry scraping, very slightly arc the entire edge as shown.

Rounding the corners will help keep you from making gouge lines

on the surface you're scraping. Arcing an edge will give you

better bite for dry scraping.

Keep your file with you at all times. Dry scraping necessitates

resharpening as often as every half minute. Heat scraping

necessitates resharpening about every five minutes.

Use a variety of motions with your scraper - towards the guns

with the grain, away from the guns with the grain, perpendicular

to the grain, and diagonal to the grain.

Take your time and let the heat do most of the work, or

you'll end up with gouges on your wood surfaces. Clean up

all residue as you go along.

Heat assisted scraping is usually the best approach even

when just spot scraping. It's gentler on the wood and will

allow you to feather the paint as you go along.

Retire your blade as soon as it becomes a bit of a chore

to sharpen it. (You get to the thicker part of the blade

as you sharpen it.) The cost of the files and scraper

blades is small compared to the cost of struggling with

expended files and blades.

Here is a great dry scraping tip for fast paint removal,

especially when the paint is stubbornly attached: Use the

round edge of your blade to make channels in the surface.

Space these parallel channels about 1/3 of an inch apart.

Then come back over it with the flat blade. Presto - you

can strip any thick stubborn paint with very little muscle.

The only catch is that it sometimes leaves a somewhat crude

surface. Be careful of where and how you use this technique.

6. Sinking nails

Setting nails needs to be done after heat stripping and before

sanding.

I found that I couldn't set nails for very long unless I used a

vice-grips to hold the nail set, as my fingers gave out. Better

yet, grind the ball of a ball-peen hammer into the shape of a nail

set. Then use another hammer to strike the ball-peen hammer. You

can really fly along with this method. It's been my method for

the past twenty years.

Here is a great dry scraping tip for fast paint removal,

especially when the paint is stubbornly attached: Use the

round edge of your blade to make channels in the surface.

Space these parallel channels about 1/3 of an inch apart.

Then come back over it with the flat blade. Presto - you

can strip any thick stubborn paint with very little muscle.

The only catch is that it sometimes leaves a somewhat crude

surface. Be careful of where and how you use this technique.

6. Sinking nails

Setting nails needs to be done after heat stripping and before

sanding.

I found that I couldn't set nails for very long unless I used a

vice-grips to hold the nail set, as my fingers gave out. Better

yet, grind the ball of a ball-peen hammer into the shape of a nail

set. Then use another hammer to strike the ball-peen hammer. You

can really fly along with this method. It's been my method for

the past twenty years.

The nail set holes are filled with a low shrinkage elastic

filler after the initial wood priming. A good general purpose

filler is clear siliconized acrylic caulk with Durabond

joint-compound powder added to greatly reduce the water content,

which in turn greatly reduces shrinkage. Two applications are

typically needed. Allow some cure time before applying any

coating over it. Be sure to use the clear caulk to

minimize its capacity to absorb moisture during its service

life.

And as long as you keep the mixture wrapped in plastic, it

will have an indefinitely long shelf life. This mixture

can also be used to fill very large cavities where you've

carved away rotted wood, sparing you many minor carpentry

tasks. Be sure to apply polyurethane caulk, such as Vulkem,

to the wood surfaces of large cavities prior to applying

the patching compound to prevent the moisture in the

patching compound to degrade the wood fibers, as the

moisture will be present for a long while when making deep

patches.

A less elastic filler is epoxy with Durabond joint compound

added. Though lacking in elasticity, this filler does have the

advantage of absorbing virtually no moisture even under extreme

conditions. This means that it won't release excessive

moisture during periods of rapid moisture evaporation through

the paint film, such as when a hot afternoon sun heats up a

dark colored topcoat. If that dark colored topcoat has much of

a sheen, it could blister where excessive moisture tries to

quickly escape. However, epoxy fillers are very time consuming

and fussy to work with. I gave that method a thorough test

on three occasions, and finally said "never again" except in

such case as noted above.

Sometimes siding boards are so dense and the nail heads so

large that setting is impractical if not impossible. In

those cases the nail heads will need a very heavy spot priming

with red iron oxide rust primer prior to applying the wood

primer. They will also need a very careful finger-wipe

caulking after the wood primer is applied, or else water will

surely enter the surface here and cause premature paint

failure.

7. Hand sanding

60 grit floor-sanding paper works well for all exterior hand

sanding tasks. Not only is it very long lasting, but it is

stiff and thus works very well on corners and narrow

surfaces. It can also be formed into a stiff rolled

shape for doing tight concave surfaces.

For a little more money, you can avoid getting slivers

(no small issue) by using sponge sanding blocks. They are

also long lasting and come in coarse, medium and fine grit.

The problematic and most frequent slivers are the ones

that go under your fingernails.

Wearing cotton gloves while sanding with the floor-sanding

paper is another means to avoid such slivers. I've become

adept at not getting under-the-fingernail slivers by virtue

of always keeping my fingers perpendicular to the sanding

motion, and have no need for gloves or sanding blocks.

If you were gentle with the scraper and let the heat do

most of the work as you heat stripped, and if you carefully

scraped off all the residue as you went along, then a good

stiff hand sanding will complete the stripping task.

Of particular importance is the rounding of the underside

of each siding board, as well as the edges of all trim boards.

A paint film is compromised by sharp edges.

Blow dust off the wood and out of nail holes with a reversed

vacuum or leaf blower before priming.

The nail set holes are filled with a low shrinkage elastic

filler after the initial wood priming. A good general purpose

filler is clear siliconized acrylic caulk with Durabond

joint-compound powder added to greatly reduce the water content,

which in turn greatly reduces shrinkage. Two applications are

typically needed. Allow some cure time before applying any

coating over it. Be sure to use the clear caulk to

minimize its capacity to absorb moisture during its service

life.

And as long as you keep the mixture wrapped in plastic, it

will have an indefinitely long shelf life. This mixture

can also be used to fill very large cavities where you've

carved away rotted wood, sparing you many minor carpentry

tasks. Be sure to apply polyurethane caulk, such as Vulkem,

to the wood surfaces of large cavities prior to applying

the patching compound to prevent the moisture in the

patching compound to degrade the wood fibers, as the

moisture will be present for a long while when making deep

patches.

A less elastic filler is epoxy with Durabond joint compound

added. Though lacking in elasticity, this filler does have the

advantage of absorbing virtually no moisture even under extreme

conditions. This means that it won't release excessive

moisture during periods of rapid moisture evaporation through

the paint film, such as when a hot afternoon sun heats up a

dark colored topcoat. If that dark colored topcoat has much of

a sheen, it could blister where excessive moisture tries to

quickly escape. However, epoxy fillers are very time consuming

and fussy to work with. I gave that method a thorough test

on three occasions, and finally said "never again" except in

such case as noted above.

Sometimes siding boards are so dense and the nail heads so

large that setting is impractical if not impossible. In

those cases the nail heads will need a very heavy spot priming

with red iron oxide rust primer prior to applying the wood

primer. They will also need a very careful finger-wipe

caulking after the wood primer is applied, or else water will

surely enter the surface here and cause premature paint

failure.

7. Hand sanding

60 grit floor-sanding paper works well for all exterior hand

sanding tasks. Not only is it very long lasting, but it is

stiff and thus works very well on corners and narrow

surfaces. It can also be formed into a stiff rolled

shape for doing tight concave surfaces.

For a little more money, you can avoid getting slivers

(no small issue) by using sponge sanding blocks. They are

also long lasting and come in coarse, medium and fine grit.

The problematic and most frequent slivers are the ones

that go under your fingernails.

Wearing cotton gloves while sanding with the floor-sanding

paper is another means to avoid such slivers. I've become

adept at not getting under-the-fingernail slivers by virtue

of always keeping my fingers perpendicular to the sanding

motion, and have no need for gloves or sanding blocks.

If you were gentle with the scraper and let the heat do

most of the work as you heat stripped, and if you carefully

scraped off all the residue as you went along, then a good

stiff hand sanding will complete the stripping task.

Of particular importance is the rounding of the underside

of each siding board, as well as the edges of all trim boards.

A paint film is compromised by sharp edges.

Blow dust off the wood and out of nail holes with a reversed

vacuum or leaf blower before priming.

Part II

The Coatings

Outline:

* A conditioning soaking coat.

* Caulking and filling.

* A primer to complete the moisture seal.

* Finish coats primarily for sunlight protection.

* Encapsulation

Overview:

Start with a thin product with good sealing properties,

heavily applied in the shade. Follow with another coat

with good sealing properties to make sure the wood always

stays relatively isolated from outside moisture. Finish

with a topcoat with good permeability (good breather).

The topcoat is more for sunlight protection than for

moisture protection.

8. The Soaker Coat

I use only clear water-borne bonding primers as my

initial wood conditioner/sealer. Oil based primers, even

when thinned out and applied heavily for maximum soak,

are not the slightest bit elastic and cannot accommodate

substrate movement, especially when the substrate is

old dry wood, broad thin lumber, poorly cut lumber,

plywood or pine.

Clear water-borne bonding primers have good penetration,

and have the additional property of being able to stabilize

old dry cracked wood. They do this by sending their three-

dimensionally elastic molecules into the pores of the wood

and by winding their way through every crack in the wood,

forming a continuous elastic barrier against water. These

primers create success where oil based primers fail.

The difference is dramatic.

(Here-after referred to as clear sealer.)

My current favorite clear sealer is one made by KILZ.

The product front label includes all the following:

KILZ KLEAR

INTERIOR|EXTERIOR PRIMER

CLEAR SEALER & BONDING PRIMER

It is a very thin product, is not expensive, and

stains the wood nicely -- indication of a strong chemical

reaction with the wood.

Be absolutely certain to flood it onto the surface,

preferably in the shade. Remember, you get only one

chance to soak the wood properly.

The KILZ clear sealer is not for use below 50 degrees

Fahrenheit. For temperatures between 35 and 50, you

could use XIM PeelBond or a mixture of three parts

XIM Peelbond to one part Sherwin Williams semi-transparent

(clear base) untinted Woodscapes. (Woodscapes provides

urethane content. Do not increase the amount of Woodscapes

in the mixture, or you could have adhesion problems

with the next coat of primer. If you plan on delaying

the next coat for more than a day during warm sunny

weather, just use straight XIM PeelBond or other

off-the-shelf clear sealer.)

Dry gray wood indicates surface rot. Sand it away, since

the wood fibers are very weak when gray and can fail,

taking the paint off with it of course.

Be sure to apply your next coat (a pigmented acrylic

primer) over the clear sealer as soon as you reasonably

can, both to ensure good adhesion and to avoid break-

down of the clear sealer from sunlight.

For surfaces that are a complex mixture of bare wood

and existing paint, making spot priming impractical,

an alkyd primer might be okay when the existing paint

is alkyd or oil base, but an acrylic primer/sealer

should be used when the existing paint is latex.

It's always a risk to apply alkyd primer or alkyd paint

over latex paint. The reasons for this are not chemical

incompatibility but rather mechanical considerations: You

don't want a coating which is a very poor breather over a

coating which is a good breather, as this can lead to

moisture buildup in the good breathing coat and ultimate

failure. You also don't want a coating with little

elasticity over a coating of high elasticity, as this can

lead to alligatoring.

9. Caulking and filling

The caulking and nail hole filling is performed next,

allowing you to apply two film forming coats over it.

The best caulk is DAP 40 year siliconized acrylic. Caulk

every little crack, tiny hole and end joint, however tight

the joint may be.

You should use a polyurethane caulk, such as Vulkem, for

high movement "architectural joints", such as where fascia

and crown moulding meet at outside corners. Allow plenty

of drying time.

This is also the point at which filling the nail holes is

performed. See section 6 (sinking nails) above.

Another excellent use for the DAP 40 year caulk is as window

glazing. I resisted this method for years because I was

proud of my traditional glazing skills. But caulk will

outlast glazing by dozens of years, will remove far more

easily should you need to replace a window pane, will save

a considerable amount of time right up front, and will have

a nice appearance once you become proficient at

applying it. It's been a frequent method of mine for many

years -- it depends on the particular project. After

applying the caulk, run your little finger along it in a

pushing manner. Be sure to prime the mullions prior to

glazing. Also be sure to razor away existing paint from

the window glass prior to priming and glazing. Use the

DAP white caulk for glazing.

10. Second coat - The Acrylic Primer

After caulking you are ready for your second coat of

primer, as the clear sealer alone is not adequate

moisture protection for the wood.

All coatings, from the initial sealer to the finish coats,

need to be elastic.

This is especially important whenever the wood has a high

degree of instability, such as in the case of old dry

cracked wood, plywood, poor cut wood, broad soft boards,

or pine.

A pigmented acrylic primer such as 1-2-3 by Zinnser

works well over the penetrating coat. This primer

will provide pretty good film build and provide both

moisture protection and the beginning of sunlight

protection. This coating needs to be applied heavily

if it's going to do its work. Be very careful to not

brush it beyond what is necessary -- it is more sensitive

to overbrushing than other acrylic products. Window sills

need an extra coat.

1-2-3 is a truly remarkable product. Its combination of

bonding, sealing, hiding and elasticity is ideal. It is

remarkably low in price and is available at all types of

stores. I don't know where I'd be without it. It is the

only acrylic primer I ever use (not counting the clear

sealers).

If there is bleeding present after the clear sealer has

been applied, a coat of 1-2-3, or in extreme cases, multiple

light coats of 1-2-3, would handle that as well. Adding

yellow oxide to 1-2-3 makes it more effective against tannin

bleeding in cedar. (The tinting base of 1-2-3 does not

provide good protection against tannin bleeding.)

11. Finish Coats

Ben Moore exterior finish coats

I use Ben Moore Element Guard Lifetime Coating or Sherwin-

Williams Duration exclusively.

These coatings are better bonding, more elastic, coatings

than previous premium acrylic coatings and are the ultimate

finish coat for exterior painting. (Duration is higher build

than Element Guard.)

(I'm currently using Element Guard, so will hereafter refer

just to that.)

Element Guard performs well down to 35 degrees. I do not rely

on it for general bare wood priming, since most situations call

for better penetration, sealing or stabilization. Disregard any

information on the label or advice you get from the paint store

regarding the use of Element Guard or any other paint as a

primer. A fully pigmented product such as house paint cannot

possibly penetrate wood cells or enhance wood fibers the way a

dedicated primer can. It is no wonder that I've seen other

painters' coatings fail when they've used Element Guard or

Duration as a wood primer.

Element Guard can be used as a two coat system over the clear

sealer, but using 1-2-3 as the next coat over the clear sealer

will provide better moisture protection, as well as bleeding

protection as mentioned above. (Also see the final paragraph

of section 10.)

I use eggshell (low luster) acrylic paint for exteriors whenever

I can, as opposed to flat, semigloss or even satin-finish.

Eggshell finishes have just the right resin/pigment ratio to

allow the paint to both breath and shed water. Ideally, the

topcoats should breath better than the primer(s) in order to

avoid moisture trapping.

The semigloss -- and even the satin-finish -- are particularly

risky when using a dark color, as a hot afternoon sun can

cause it to blister, particularly if that hot sun was preceded

by a period of damp weather (which creates moisture buildup in

the substrate). It's unpredictable.

There is a strong tendency for people to overbrush acrylic

coatings and to spread the coating too far. One goal is

to apply a film of protection on the surface, not to

just color the surface. Another goal is to transfer the

acrylic substance from the can to the surface in a

uniform film with as little disturbance of the resin as

possible -- this is what ensures long term film service.

There should be a minimum of three coats of film-forming

product everywhere (except well shaded soffits). This

might take the form of a clear sealer followed by two coats

of Element Guard, or a clear sealer followed by 1-2-3

acrylic primer, then Element Guard.

Anything less does not adequately seal the surface.

When moisture penetrates into the wood often, the surface

wood fibers lose their integrity and the film fails at

the wood surface, ultimately as the result of hydrostatic

pressure (the pressure of water evaporation) acting on

what has become a poor bond.

Adequately sealing the surface is important even for

short term success.

A four-coat system is recommended on siding if you are

spraying. Brush on the clear sealer and 1-2-3, then

spray two coats of Element Guard, with one coat sprayed

slightly upward and the other coat sprayed slightly

downward.

Soffits require less protection. For well shaded soffits

that have only a small percentage of bare wood exposed

after scraping, you could actually get by with just a one

coat process: mix one part Penetrol or Emulsa Bond with

three parts acrylic finish coat. This gives the coating

better sealing and surface wetting properties. (Penetrol

mixes with latex paint just as well as Emulsa Bond and

provides the same long term performance. I always have

Penetrol in stock and therefore use it exclusively.)

To review: I favor the all-acrylic systems even when the

existing substrate is oil based. I rely on the clear sealer

as a whole house initial primer, over bare wood of course,

but also over chalky paint (brush or back-brush so as

to make sure the sealer penetrates the chalk all the way to

the underlying substrate) and checked paint (if sound). It

binds any residual dirt on the surface that pressure washing

leaves behind and even helps rejuvenate the surface of an old

acrylic paint film. The fact that the clear sealer is very

low in pigment allows it to bind chalk and dirt.

12. Encapsulation

Encapsulation can be regarded as stabilizing a substrate,

whether the substrate is bare wood or old paint.

Problem boards

Boards with horizontal hairline cracks as well as larger

cracks need to have a high stretch caulk (DAP 40-year)

troweled into their cracks.

There can be over a hundred such areas on a house with these

types of lumber problems, and replacing all such boards can

be cost prohibitive, especially when dealing with fascia

boards and crown molding, the very boards that most

frequently have long running cracks.

Old checked paint

This section examines the concept of layering coatings

for optimal encapsulation of old checked paint.

I use the system described below primarly in the

following areas:

The siding and trim at the first floor level on the

front of a house that is well protected by a porch

ceiling.

Low soffits and low frieze boards that are well

protected by soffits. This typically means frieze

boards on both the inside and outside of a porch.

Siding and trim at the first floor level on the north

side of a house. (North sides degrade more slowly,

and the first floor level is the most visible, being

at eye-level.)

For checked paint in other areas (more exposed to

weathering and/or less visible), I simply use a lower-

stretch paint than Element Guard.

First of all, one needs to learn to recognize the difference

between stable and unstable old paint. Generally speaking,

if the paint is not separating from the substrate or even

hinting at it, then the paint is stable, even if heavily

checked.

But checked paint can become unstable if not encapsulated

correctly:

It's desirable to use a very elastic final coat over the

checked paint, or else the checking will transmit through

it in time.

Unfortunately, a coating which is sufficiently elastic to

accomplish that might also pull the old coating loose from

the substrate through repeated expansion and contraction

with temperature changes.

Applying an oil based primer over the checked paint

prior to an elastic coating will not solve the problem,

because the elastic coating will still do work on the checked

paint by virtue of transmitting its force very effectively

through the relatively inelastic coat of new oil primer.

What to do? The secret is in using a go between coating

that is not elastic enough to flex the checked paint loose,

but elastic enough to force the elastic topcoat to do much

of its work on the go between coating. The flex force of

the elastic topcoat is largely dissipated in the go-between

coating.

I find the definition of the paint film attribute "elongation"

to be misleading: A paint film with an elongation factor

of 1 means it will stretch to 2 times its original length before

tearing. An elongation factor of 2 means it will stretch to

3 times its original length before tearing. So I use a term

called "stretch factor" to distinguish it from the industry

defined term - "elongation", even though it's the exact same

concept.

A coating with a stretch factor of 1 means that the coating

will tear upon trying to stretch it beyond its original length

of 1 unit. A coating with a stretch factor of 2 means it will

tear when stretched to double its original length.

Here are some examples among quality exterior coatings:

Sherwin Williams Superpaint flat 1.3

Benjamin Moore Moorlife flat 1.5

Benjamin Moore Moorgard eggshell 1.5

Zinsser 1-2-3 acrylic primer 1.6

Sherwin Williams Superpaint satin 2.1

Ben Moore Element Guard low luster 2.5

Sherwin Williams Duration low luster 2.8

(Low Luster = eggshell)

These numbers are approximate values, based on averaging

my test samples using white or light colors.

I've had good success in long-term encapsulation using

paint or primer with a stretch factor of between 1.3 and

1.6 as my buffer coat, but prefer the low end of this range.

It must be applied heavily or in two coats (1.3, then 1.6)

to be most effective. Start with a light coat of the clear

sealer, especially if there is any bare wood mingled with the

checked paint. It's function is to seal the wood and bind

any dust on the surface. It's thin film will not play a role

in the stability of the checked paint one way or the other.

(It has a stretch factor of 1.5.)

A light coat of Element Guard is of course my choice for the

final coat over the buffer coat(s).

I rarely see failure upon returning to inspect old job

sites where this method was used.

-----------------------------------------------------------

When I encounter chinzy plywood veneer siding (faux

vertical tongue & groove), with its current or future

hairline cracks, I increase the elasticity of Element Guard

or Duration by mixing equal parts DAP clear Dynaflex 230

(stretch factor = 6.0) with Element Guard or Duration. This

yields a stretch factor of 4.3. Anything less will not

bridge the hairline cracks permanently. Apply two coats,

then finish with Element Guard or Duration.

-----------------------------------------------------------

13. Overpainting

When paint separates from the substrate, there is always

hydrostatic pressure involved. This is the pressure of

water evaporation. To reduce the possibility of this occurring,

you must use coatings with a favorable ratio of adhesion to

permeability, you must apply them in the correct order, and

you must not overcoat a surface.

A heavy build up of coatings over the years can work against

you in two ways:

When the permeability of the overall coating system reaches

a certain low point, the film will separate at the weakest link,

usually at the surface of the wood, especially if the initial

primer did not penetrate deeply enough into the wood or did not

enhance the wood fibers.

Also, as the total thickness increases, the elasticity decreases,

leading to cracks in the film.

Which is the biggest problem is hard to say.

To review what was said earlier about primers and topcoats:

Start with a product with good sealing properties, heavily

applied in the shade. Follow with another coat with

good sealing properties to make sure the wood always stays

relatively isolated from outside moisture. Finish with a

topcoat with good permeability (good breather). The topcoat

finalizes the moisture protection and provides sunlight

protection.

When encapsulating old paint, there is risk of creating

hydrostatic pressure beyond what the old coating can resist,

but that can sometimes be a good risk management decision,

considering the cost of paint removal.

Note:

On some projects, I've removed and reinstalled all

the siding back side out, running each piece through

a table saw to remove the paint from the bottom edge.

I hand sand or power sand the face to freshen it. The

total time required is about the same as for stripping

with the triple heat gun as described above. If you are

handy with a flat pry bar, you can remove all the siding

with no damage. It's important to grind down your flat

pry bar until it is very sharp and has a very slim profile

over the first couple of inches.

Reversing the siding works only if your house has

vertical corner boards, or if you are willing to

install corner boards. Otherwise the bevels at the

corners will be backwards. I once converted a house

to vertical corner boards and it went very smoothly.

Mark the locations of each siding board on the adjacent

window frame or corner board prior to removal. Scrape

the edge of the window frame or corner board clean of

paint so that you can pry off the siding boards without

binding.

Work from the top down. Use a specialty pry bar to

extract the nails from the top two or three siding

boards. It is smooth sailing the rest of the way.

Page updated on 08/28/2025.

contact:

roger@rogcad.com

r luebeck home page <-- back to

|

I've been restoring old houses in Minneapolis since 1976, with an interest in the permanence of the restoration. I've done 100 percent paint removal and recoating on scores of large houses, using heat guns. I use only Ben Moore Element Guard or Sherwin Williams Duration. I also perform the carpentry tasks. The photo above and below is my standard fare on exteriors.

4. The heat gun

4. The heat gun

I've carefully measured stripping progress using single,

double and triple heat guns, and consistently find that

double heat guns strip at exactly twice the rate of single

guns, and triple heat guns strip at exactly triple the rate

of single guns.

Triple guns work well for siding. I buy the thirty-dollar

guns at Menards or Home Depot, remove the plastic casing

from two of them, and through the use of electrical or

duct tape, achieve the configuration in the photo. By

doing this and by fastening the cords at your waist, you

will reduce the weight to exactly that of two heat guns.

A very important modification of the nozzle is to make about

a dozen snips and flare out the resulting sections as shown

in the photo. This will not only spread the heat out more

uniformly on the surface to be stripped, it will also allow

you to hold the nozzles right up against the surface and

keep them there. The biggest mistake workers make when

using heat guns is that they tend to keep backing the gun

away from the surface. The nozzles should rest on the

surface 100 percent of the time you are stripping.

Work in long strips. Heat spreads through the paint film

by conduction. If you work in short strips, you lose this

advantage of preheating. You also lose this advantage

every time you back the gun off the surface.

Double heat guns work well for trim and siding. Simply tape

two guns together.

Each heat gun requires a separate electrical circuit. Have

lots of cord on hand. Each 1000 watt gun costs fifteen cents

per hour to run. Thus, a triple gun costs less than four

dollars per day to operate.

Fire hazards

Heat stripping does not need to be a risky procedure. The

most important thing is to carefully caulk all cracks,

holes and gaps between boards before using heat. Carefully

inspect under each siding board as well as all other boards

for gaps, holes or cracks.

Hidden fires in walls, eaves and under shingles start

in two ways:

1. Heat flowing into cracks, holes or gaps.

There is very dry wood or even dry wood dust in

walls, eaves, and at the roof line. This can

begin to smolder without your knowledge and erupt

into flames after you've gone home.

2. Sparks emitted from heat gun nozzles drift into

cracks, holes or gaps.

Bits of paint shavings fall into the nozzles and

come out as sparks, particularly when melting on

the underside of a horizontal surface, such as a

soffit.

You can virtually eliminate the risk of fire by using caulk

to fill in any cracks, holes or gaps prior to heat stripping.

This is my standard procedure. Never aim your gun at or below

any crack, hole or gap.

One place that cannot be caulked is where the roof shingles

meet the fascia board. Stay well away from the roof line

when heat stripping. Dry scrape the upper couple inches of

the fascia board.

Whenever in doubt, turn the guns down to the low heat setting

or back them well away from the surface and use a little extra

scraping muscle.

Keep a water hose with nozzle attachment, a hammer and a

pry bar near you on your scaffolding. The hose should be left

on at the spicket. (A small fire extinguisher is very handy.)

In the event of a fire, do not pry up any board until you have

the hose in hand. Prying up a board gives the fire a burst of

oxygen and sudden life, causing it to spread rapidly.

4.5 Infrared heat (radiant heat) for paint removal

Another possibility to consider:

A lightweight infrared heater using just one electrical

circuit strips paint nearly as fast as my triple circuit

heat guns, provided there is reasonable continuity of the

paint film to be stripped. I began using infrared heat

occasionally, beginning in 2004, after being alerted to it by

a reader of this website. It's been a nice compliment to

my old standby conventional heat guns. The drawback is that

there is a slow initial heat transfer to the substrate,

meaning it is all the more important to keep the tool on

the substrate continuously.

I haven't seen evidence of any fire hazard with it (but

still use caution), and little or no need of a face mask.

Why no one thought of this for paint removal 50 years ago is

hard to understand. The technology is at least that old.

There is a commercial model available, but I didn't want

to spend $465 on the heavy commercial model when I could

make a lightweight model for about $50 in materials and

30 minutes of my time. I converted an old infrared room heater

for which I had paid about $50 into a very lightweight paint

remover. The replacement tubes are only $10 (and I have yet to

burn out a tube).

My tool works as well as the commercial model. The working

parts in my tool are the same as in the commercial model -

two quartz tubes.

Go to wbmarvin.com for a listing of available infrared

heaters and the $10 replacement tubes. The model 5460

Steam 'n Heat at $79.95 looks like the current version of the

old Marvin heater I had used to make my paint remover. You

might also check at Walmart or search online for inexpensive

infrared quartz room heaters.

Make your own infrared paint remover and save the weight and

the high cost of the commercial model. The commercial model

(Silent Paint Remover) weighs 4 lb 3 oz. My infrared paint

remover weighs just 1 lb 12 oz. This includes the 12 oz

clamp being used for the handle. A lighter handle, such as

a simple L-shaped piece of wood will bring the weight down

to just 1 lb 1 oz. Having stripped paint for a living for

the past 50 years using heat guns, I can assure you that

you'll appreciate this weight reduction and increased

productivity.

I've carefully measured stripping progress using single,

double and triple heat guns, and consistently find that

double heat guns strip at exactly twice the rate of single

guns, and triple heat guns strip at exactly triple the rate

of single guns.

Triple guns work well for siding. I buy the thirty-dollar

guns at Menards or Home Depot, remove the plastic casing

from two of them, and through the use of electrical or

duct tape, achieve the configuration in the photo. By

doing this and by fastening the cords at your waist, you

will reduce the weight to exactly that of two heat guns.

A very important modification of the nozzle is to make about

a dozen snips and flare out the resulting sections as shown

in the photo. This will not only spread the heat out more

uniformly on the surface to be stripped, it will also allow

you to hold the nozzles right up against the surface and

keep them there. The biggest mistake workers make when

using heat guns is that they tend to keep backing the gun

away from the surface. The nozzles should rest on the

surface 100 percent of the time you are stripping.

Work in long strips. Heat spreads through the paint film

by conduction. If you work in short strips, you lose this

advantage of preheating. You also lose this advantage

every time you back the gun off the surface.

Double heat guns work well for trim and siding. Simply tape

two guns together.

Each heat gun requires a separate electrical circuit. Have

lots of cord on hand. Each 1000 watt gun costs fifteen cents

per hour to run. Thus, a triple gun costs less than four

dollars per day to operate.

Fire hazards

Heat stripping does not need to be a risky procedure. The

most important thing is to carefully caulk all cracks,

holes and gaps between boards before using heat. Carefully

inspect under each siding board as well as all other boards

for gaps, holes or cracks.

Hidden fires in walls, eaves and under shingles start

in two ways:

1. Heat flowing into cracks, holes or gaps.

There is very dry wood or even dry wood dust in

walls, eaves, and at the roof line. This can

begin to smolder without your knowledge and erupt

into flames after you've gone home.

2. Sparks emitted from heat gun nozzles drift into

cracks, holes or gaps.

Bits of paint shavings fall into the nozzles and

come out as sparks, particularly when melting on

the underside of a horizontal surface, such as a

soffit.

You can virtually eliminate the risk of fire by using caulk

to fill in any cracks, holes or gaps prior to heat stripping.

This is my standard procedure. Never aim your gun at or below

any crack, hole or gap.

One place that cannot be caulked is where the roof shingles

meet the fascia board. Stay well away from the roof line

when heat stripping. Dry scrape the upper couple inches of

the fascia board.

Whenever in doubt, turn the guns down to the low heat setting

or back them well away from the surface and use a little extra

scraping muscle.

Keep a water hose with nozzle attachment, a hammer and a

pry bar near you on your scaffolding. The hose should be left

on at the spicket. (A small fire extinguisher is very handy.)

In the event of a fire, do not pry up any board until you have

the hose in hand. Prying up a board gives the fire a burst of

oxygen and sudden life, causing it to spread rapidly.

4.5 Infrared heat (radiant heat) for paint removal

Another possibility to consider:

A lightweight infrared heater using just one electrical

circuit strips paint nearly as fast as my triple circuit

heat guns, provided there is reasonable continuity of the

paint film to be stripped. I began using infrared heat

occasionally, beginning in 2004, after being alerted to it by

a reader of this website. It's been a nice compliment to

my old standby conventional heat guns. The drawback is that

there is a slow initial heat transfer to the substrate,

meaning it is all the more important to keep the tool on

the substrate continuously.

I haven't seen evidence of any fire hazard with it (but

still use caution), and little or no need of a face mask.

Why no one thought of this for paint removal 50 years ago is

hard to understand. The technology is at least that old.

There is a commercial model available, but I didn't want

to spend $465 on the heavy commercial model when I could

make a lightweight model for about $50 in materials and

30 minutes of my time. I converted an old infrared room heater

for which I had paid about $50 into a very lightweight paint

remover. The replacement tubes are only $10 (and I have yet to

burn out a tube).

My tool works as well as the commercial model. The working

parts in my tool are the same as in the commercial model -

two quartz tubes.

Go to wbmarvin.com for a listing of available infrared

heaters and the $10 replacement tubes. The model 5460

Steam 'n Heat at $79.95 looks like the current version of the

old Marvin heater I had used to make my paint remover. You

might also check at Walmart or search online for inexpensive

infrared quartz room heaters.

Make your own infrared paint remover and save the weight and

the high cost of the commercial model. The commercial model

(Silent Paint Remover) weighs 4 lb 3 oz. My infrared paint

remover weighs just 1 lb 12 oz. This includes the 12 oz

clamp being used for the handle. A lighter handle, such as

a simple L-shaped piece of wood will bring the weight down

to just 1 lb 1 oz. Having stripped paint for a living for

the past 50 years using heat guns, I can assure you that

you'll appreciate this weight reduction and increased

productivity.

I refolded the aluminum reflector so that the tubes would

be spaced 2 1/2 inches apart, which is the average spacing

of narrow lap siding.

I also made a single tube model for doing narrow architectural

detail.

Neither the aluminum reflector or the clamp get too warm

to cause any problem. I casually lay the tool down facing

up and running (meaning plugged in - no switch needed) when

I'm not using it. You can lay it down on any surface such

as a wood plank, the ground, or a nylon tarp.

5. Pro-Prep scrapers

I refolded the aluminum reflector so that the tubes would

be spaced 2 1/2 inches apart, which is the average spacing

of narrow lap siding.

I also made a single tube model for doing narrow architectural

detail.

Neither the aluminum reflector or the clamp get too warm

to cause any problem. I casually lay the tool down facing

up and running (meaning plugged in - no switch needed) when

I'm not using it. You can lay it down on any surface such

as a wood plank, the ground, or a nylon tarp.

5. Pro-Prep scrapers

These scrapers will not only greatly boost your heat stripping

output, they will be your partner in all kinds of dry scraping

endeavors, from high speed outdoor dry paint removal to fine

interior wood refinishing projects, including furniture.

Proper sharpening and use of these scrapers is at the heart

of indoor and outdoor refinishing projects. The blades shown

above will be your primary ones for outdoor work (and most

indoor work). For heat stripping, I use the small sized

handles even with the large sized blades. This gives greater

clearance for shavings.

Buy large coarse grade files by the half-dozen, or by the

dozen if you have a helper. A sharp file is the only tool

to use to sharpen your scraper. As soon as filing becomes

a bit of a struggle, throw the file away.

These scrapers will not only greatly boost your heat stripping

output, they will be your partner in all kinds of dry scraping

endeavors, from high speed outdoor dry paint removal to fine

interior wood refinishing projects, including furniture.

Proper sharpening and use of these scrapers is at the heart

of indoor and outdoor refinishing projects. The blades shown

above will be your primary ones for outdoor work (and most

indoor work). For heat stripping, I use the small sized

handles even with the large sized blades. This gives greater

clearance for shavings.

Buy large coarse grade files by the half-dozen, or by the

dozen if you have a helper. A sharp file is the only tool

to use to sharpen your scraper. As soon as filing becomes

a bit of a struggle, throw the file away.

Place the scraper on a firm surface and file into the blade

edge. File at a 45 degree angle. Slightly round the corners

of the large flat blades as shown in the drawing; and for

dry scraping, very slightly arc the entire edge as shown.

Rounding the corners will help keep you from making gouge lines

on the surface you're scraping. Arcing an edge will give you

better bite for dry scraping.

Keep your file with you at all times. Dry scraping necessitates

resharpening as often as every half minute. Heat scraping

necessitates resharpening about every five minutes.

Use a variety of motions with your scraper - towards the guns

with the grain, away from the guns with the grain, perpendicular

to the grain, and diagonal to the grain.

Take your time and let the heat do most of the work, or

you'll end up with gouges on your wood surfaces. Clean up

all residue as you go along.

Heat assisted scraping is usually the best approach even

when just spot scraping. It's gentler on the wood and will

allow you to feather the paint as you go along.

Retire your blade as soon as it becomes a bit of a chore

to sharpen it. (You get to the thicker part of the blade

as you sharpen it.) The cost of the files and scraper

blades is small compared to the cost of struggling with

expended files and blades.

Place the scraper on a firm surface and file into the blade

edge. File at a 45 degree angle. Slightly round the corners

of the large flat blades as shown in the drawing; and for

dry scraping, very slightly arc the entire edge as shown.

Rounding the corners will help keep you from making gouge lines

on the surface you're scraping. Arcing an edge will give you

better bite for dry scraping.

Keep your file with you at all times. Dry scraping necessitates

resharpening as often as every half minute. Heat scraping

necessitates resharpening about every five minutes.

Use a variety of motions with your scraper - towards the guns

with the grain, away from the guns with the grain, perpendicular

to the grain, and diagonal to the grain.

Take your time and let the heat do most of the work, or

you'll end up with gouges on your wood surfaces. Clean up

all residue as you go along.

Heat assisted scraping is usually the best approach even

when just spot scraping. It's gentler on the wood and will

allow you to feather the paint as you go along.

Retire your blade as soon as it becomes a bit of a chore

to sharpen it. (You get to the thicker part of the blade

as you sharpen it.) The cost of the files and scraper

blades is small compared to the cost of struggling with

expended files and blades.

Here is a great dry scraping tip for fast paint removal,

especially when the paint is stubbornly attached: Use the

round edge of your blade to make channels in the surface.

Space these parallel channels about 1/3 of an inch apart.

Then come back over it with the flat blade. Presto - you

can strip any thick stubborn paint with very little muscle.

The only catch is that it sometimes leaves a somewhat crude

surface. Be careful of where and how you use this technique.

6. Sinking nails

Setting nails needs to be done after heat stripping and before

sanding.

I found that I couldn't set nails for very long unless I used a

vice-grips to hold the nail set, as my fingers gave out. Better

yet, grind the ball of a ball-peen hammer into the shape of a nail

set. Then use another hammer to strike the ball-peen hammer. You

can really fly along with this method. It's been my method for

the past twenty years.

Here is a great dry scraping tip for fast paint removal,

especially when the paint is stubbornly attached: Use the

round edge of your blade to make channels in the surface.

Space these parallel channels about 1/3 of an inch apart.

Then come back over it with the flat blade. Presto - you

can strip any thick stubborn paint with very little muscle.

The only catch is that it sometimes leaves a somewhat crude

surface. Be careful of where and how you use this technique.

6. Sinking nails

Setting nails needs to be done after heat stripping and before

sanding.

I found that I couldn't set nails for very long unless I used a

vice-grips to hold the nail set, as my fingers gave out. Better

yet, grind the ball of a ball-peen hammer into the shape of a nail

set. Then use another hammer to strike the ball-peen hammer. You

can really fly along with this method. It's been my method for

the past twenty years.

The nail set holes are filled with a low shrinkage elastic

filler after the initial wood priming. A good general purpose

filler is clear siliconized acrylic caulk with Durabond

joint-compound powder added to greatly reduce the water content,

which in turn greatly reduces shrinkage. Two applications are

typically needed. Allow some cure time before applying any

coating over it. Be sure to use the clear caulk to

minimize its capacity to absorb moisture during its service

life.

And as long as you keep the mixture wrapped in plastic, it

will have an indefinitely long shelf life. This mixture

can also be used to fill very large cavities where you've

carved away rotted wood, sparing you many minor carpentry

tasks. Be sure to apply polyurethane caulk, such as Vulkem,

to the wood surfaces of large cavities prior to applying

the patching compound to prevent the moisture in the

patching compound to degrade the wood fibers, as the

moisture will be present for a long while when making deep

patches.

A less elastic filler is epoxy with Durabond joint compound

added. Though lacking in elasticity, this filler does have the

advantage of absorbing virtually no moisture even under extreme

conditions. This means that it won't release excessive

moisture during periods of rapid moisture evaporation through

the paint film, such as when a hot afternoon sun heats up a

dark colored topcoat. If that dark colored topcoat has much of

a sheen, it could blister where excessive moisture tries to

quickly escape. However, epoxy fillers are very time consuming

and fussy to work with. I gave that method a thorough test

on three occasions, and finally said "never again" except in

such case as noted above.

Sometimes siding boards are so dense and the nail heads so

large that setting is impractical if not impossible. In

those cases the nail heads will need a very heavy spot priming

with red iron oxide rust primer prior to applying the wood

primer. They will also need a very careful finger-wipe

caulking after the wood primer is applied, or else water will

surely enter the surface here and cause premature paint

failure.

7. Hand sanding

60 grit floor-sanding paper works well for all exterior hand

sanding tasks. Not only is it very long lasting, but it is

stiff and thus works very well on corners and narrow

surfaces. It can also be formed into a stiff rolled

shape for doing tight concave surfaces.

For a little more money, you can avoid getting slivers

(no small issue) by using sponge sanding blocks. They are

also long lasting and come in coarse, medium and fine grit.

The problematic and most frequent slivers are the ones

that go under your fingernails.

Wearing cotton gloves while sanding with the floor-sanding

paper is another means to avoid such slivers. I've become

adept at not getting under-the-fingernail slivers by virtue

of always keeping my fingers perpendicular to the sanding

motion, and have no need for gloves or sanding blocks.

If you were gentle with the scraper and let the heat do

most of the work as you heat stripped, and if you carefully

scraped off all the residue as you went along, then a good

stiff hand sanding will complete the stripping task.

Of particular importance is the rounding of the underside

of each siding board, as well as the edges of all trim boards.

A paint film is compromised by sharp edges.

Blow dust off the wood and out of nail holes with a reversed

vacuum or leaf blower before priming.

The nail set holes are filled with a low shrinkage elastic

filler after the initial wood priming. A good general purpose

filler is clear siliconized acrylic caulk with Durabond

joint-compound powder added to greatly reduce the water content,

which in turn greatly reduces shrinkage. Two applications are

typically needed. Allow some cure time before applying any

coating over it. Be sure to use the clear caulk to

minimize its capacity to absorb moisture during its service

life.

And as long as you keep the mixture wrapped in plastic, it

will have an indefinitely long shelf life. This mixture

can also be used to fill very large cavities where you've

carved away rotted wood, sparing you many minor carpentry

tasks. Be sure to apply polyurethane caulk, such as Vulkem,

to the wood surfaces of large cavities prior to applying

the patching compound to prevent the moisture in the

patching compound to degrade the wood fibers, as the

moisture will be present for a long while when making deep

patches.

A less elastic filler is epoxy with Durabond joint compound

added. Though lacking in elasticity, this filler does have the

advantage of absorbing virtually no moisture even under extreme

conditions. This means that it won't release excessive

moisture during periods of rapid moisture evaporation through

the paint film, such as when a hot afternoon sun heats up a

dark colored topcoat. If that dark colored topcoat has much of

a sheen, it could blister where excessive moisture tries to

quickly escape. However, epoxy fillers are very time consuming

and fussy to work with. I gave that method a thorough test

on three occasions, and finally said "never again" except in

such case as noted above.

Sometimes siding boards are so dense and the nail heads so

large that setting is impractical if not impossible. In

those cases the nail heads will need a very heavy spot priming

with red iron oxide rust primer prior to applying the wood

primer. They will also need a very careful finger-wipe

caulking after the wood primer is applied, or else water will

surely enter the surface here and cause premature paint

failure.

7. Hand sanding

60 grit floor-sanding paper works well for all exterior hand

sanding tasks. Not only is it very long lasting, but it is

stiff and thus works very well on corners and narrow

surfaces. It can also be formed into a stiff rolled

shape for doing tight concave surfaces.

For a little more money, you can avoid getting slivers

(no small issue) by using sponge sanding blocks. They are

also long lasting and come in coarse, medium and fine grit.

The problematic and most frequent slivers are the ones

that go under your fingernails.

Wearing cotton gloves while sanding with the floor-sanding

paper is another means to avoid such slivers. I've become

adept at not getting under-the-fingernail slivers by virtue

of always keeping my fingers perpendicular to the sanding

motion, and have no need for gloves or sanding blocks.

If you were gentle with the scraper and let the heat do

most of the work as you heat stripped, and if you carefully